So you’re getting ready to kick off a campaign for your gaming group? Before you even get started, ask yourself: are you looking to create a campaign that will simply be fun, or one that your players will be talking about for years to come?

If your answer is the former, then you can’t go too far wrong with a well-done published campaign, with some notable exceptions. 1 Or at the very least, you can take inspiration from them in order to craft an outline and array of NPCs that can make a fun romp.

But, while this will be fun, and there will be good memories, you’ve got a lot more work to do to make it an incredible experience for your group, and if you’re putting together a homebrew campaign don’t miss the opportunity to make it something special.

#0: Meet Your Players Where They Are #

Bonus tip before we even get started!

This is an important caveat to everything else you are about to read in this guide. If your players are brand-new to TTRPGs, they may need a more pre-scripted campaign to get their feet wet, and trying to push them beyond that could make them more confused and frustrated. If you’re like me, a pre-written campaign can be a bit boring as a GM, so consider a shorter prewritten multi-session adventure and tweak it to your style to ease them into gameplay at your table.

Also keep in mind the calendar logistics of your group. [Scheduling is the true villain of any campaign, and if your players can only get together once a month, or every couple months, they are not going to be able to keep track of a complex story with many moving parts. For those cases, keep the story and tasks simple. Maybe even keep a shared doc as a Quest Log so they don’t forget what they are doing.

Everything in this guide is assuming that you’ve got a group of players who are familiar with playing TTRPGs and that you can play regularly enough that your group isn’t dependent on you to remind them of every detail of what happened from session to session.

#1: The Session Count Starts At Zero #

Do a Session Zero. I’m begging you.

Use it to figure out what kind of things your players are interested in right now. Been doing a lot of explorations across distant wastes? Maybe your players are bored with that and want an urban campaign. Maybe they want to even try out a new system. Ask questions about what they’ve enjoyed before and want more of and dig into what was less fun for them so you can figure out how to make it better. The answers may vary a lot by player, so you need all that information to make a balanced game that will satisfy everyone. If someone is looking for a game of personal horror, and someone wants a game with no RP but they get to collect the heads of mutants, you’ve got to think about that. Consider if you can accommodate for it. Everyone needs to be in agreement on what game the group is playing, but that doesn’t mean you can’t tailor experiences in a way to please personal tastes.

If you don’t think you can reconcile all the needs of the players, you should be upfront about that, and find another way to enjoy your time together. I don’t care how much you love playing TTRPGs: [A campaign needs to be fun for everyone. It’s okay for the story to be uncomfortable at times, so long as your players are down with that, but the overall experience has to be fun. It’s true that you are creating a story together, but you are still playing a game, and players that aren’t having fun will want to stop playing.

#2: Getting Consent #

OK, now you have an idea of what your players need/want that you can bump up against your own preferences to find where they match. But before you even consider the details of your campaign, you need to get a sense of the lines and veils2 of your players. You can do some of this during your Session Zero, but I’d strongly recommend you also collect this info one-on-one.

There are a lot of great tools for this, and you can find an excellent collection of them in the TTRPG Safety Toolkit which was compiled by Kienna Shaw and Lauren Bryant-Monk. My preferred tool for the pre-campaign work is the Consent in Gaming checklist, which is published by and freely available from Monte Cook Games. Some might argue you don’t need this until later in the process, but you can save yourself a ton of wasted effort if you know which themes are going to be off-limits before you even start writing.

#3: Bait the Hook Before You Pick Out a Boat #

It’s tempting to dive into world building and plotting at this point, but hold your horses. You’ll write yourself into a corner this way, and likely will end up having to redo a lot of the work later. What you need now is your pitch for your group. And it’s important to remember that at this point you are trying to sell the players on your story concept, because none of you know what might end up being compelling for their characters yet.

Your pitch should be no more than two pages, and one of the pages should simply be the proposed logistics. You want to keep your story pitch short and to the point. Your overall pitch document should give the players a sense of the following:

- The starting point, and teasing of the potential direction forward.

- The anticipated tone of the game.

- What setting is being used, and if a particular area of that setting will be in play. If it’s a home brew world, give them a couple sentences on whether it’s high/low fantasy, sci-fi, or whatever.

- How long you expect the campaign to run, and when you expect it to start. You can be a little loosey-goosey here, but the point is to make sure they have an understanding of what commitment they are making with you.

- The anticipated play schedule: weekly, biweekly, monthly, etc.3 Make sure to also specify the way the game will be played: in person, over Zoom, or using a Virtual Table Top (VTT) like Roll20/Role?

- Any exceptions to published game rules you enforce at your table.

- When characters are due and what should be turned in along with their character sheets.

- I also like to use this opportunity to recap what safety tools will be in use, though you should have gone over this already with everyone.

As an example, here’s the pitch I provided to the players of my home game before we started our current campaign, available as a PDF.

Important things to note in that doc. At no point do I tell the players anything about a BBEG or even if there is one.4 I also don’t tell them who they have to play but I do give them a sense of the world and story so they can make informed choices about their characters.

Another important thing here is requiring unanimous acceptance of the pitch. If you don’t have agreement at this stage, you’re not going to magically find it later. Save yourself hours of rewriting by figuring this part out first.

#4: Let It Simmer in Player Spices #

I bet you’re eager to get started! After crafting the pitch and chatting with your players about it, you’ve got to be chomping at the bit to start writing. But trust me, you want to wait a little longer. It’s fine to take some general notes, a few cool ideas you don’t want to forget, but the most important thing you can do right now is let the ideas marinate in your head while you wait for your players to turn in their characters.

Why? Because if you want your players to be invested in the campaign, their character backstories need to be woven through the core of the story. Note that I wrote, “core of the story”. If their character arcs are tacked-on sub-plots it’s not going to be powerful. A character’s story shouldn’t feel like a side-quest, because it’s literally the reason they are doing any of this.

Somebody has a missing sibling where the mystery of the circumstances haunts them? That better mean you are making that mystery a key part of the central plot. Maybe their twin brother is now high priest of the lich that’s currently tearing apart the kingdom. Or maybe he leads one for the factions that will be critical to win over in preparation for a final battle. Sure, the focus at any given time may be more on one character’s backstory or the other, but they all need to intimately tie into the story or its going to feel superfluous to the player, and they may check out when it’s not their character’s time in the spotlight.

I’ve built entire factions, nations, and world elements around player backstories, and you should too. A character’s backstory and individual story arc should be so intrinsic to the plot that the story depends on it for stability. If a character dies midway, **don’t ** toss out that part of the story. Leave it there. Let the players uncover clues to that arc as they progress. Even if they don’t directly pursue that part of the story anymore, the players will feel the loss more deeply and will get an even deeper understanding of how much influence they have had over the shape of your tale.

If you flesh out your campaign before you know these things, you’re going to have a harder time weaving them into the fabric of your campaign in a way that doesn’t feel cheap. Let the characters that the players turn in influence the final shape of your world and your story. Spend time talking with your players, and talk about what they would love to see their characters attempt to achieve. You can’t promise them success, but for an important enough goal, when given the time it deserves in the game, even failure can be rewarding.

As you weave the character’s backstories into your campaign, I want you to remember something very important: [The Hero’s Journey can eat a bag of dicks. Again, you’re not writing a paint-by-numbers mono-myth alone in your office. You’re telling a collaborative story, which means you don’t know what the result of each character story beat will be. You may know some exist, but don’t try to shoehorn a PC into “Call to Adventure”, “Refusal of the Call” or any of that kind of thing. 5 Give the players agency over their characters, don’t try to force them into playing out your fan fiction.

#5: Easing Your Players In #

Okay, your players have turned in their characters and backstories and you’ve got everything you need to start doing the real work of writing for your new campaign. Sketch out the primary conflicts of the core story, the major NPCs and factions that relate to it, and any lore you’re going to need to communicate to the players very early on in order to give them a chance in hell of figuring out what to do.

When it comes to breaking things down in detail, try to contain that to their first small quest (or two if you’re going to give them the option to choose between a couple). You’ll need the detail at the beginning to help immerse them into the world, and giving them a few simple choices to make early on will help them ease into their characters and get a feel for how your world works. This is true even if using a published setting. Two different GMs may run the same setting completely differently, and some GMs may run the same setting in a different way for each campaign. Give the players time to acclimate themselves.

#6: Write Stubs Instead of Paragraphs #

Even when you are outlining those early quests, don’t over-plan. You’ll never know what your players will actually do, so try not to fall into a trap of sequential encounters. Don’t waste time defining detailed conditions to achieve victory. It’s better if you don’t have a predetermined way to succeed and you let the cleverness of your players’ responses to the dilemmas you present determine whether they’ve successfully advanced past the problem.

If you’re not comfortable playing that freely as they start out, you can jot down several things that could help them resolve the issue, and just give yourself a rough guide of something like “if they can get 2/3 of these, then they can move forward.” This approach is fine for their first quest out the gate, and still gives them some autonomy in how they approach the problem, especially if you don’t explicitly lay all this out.

Now, everything I’ve said above is great for your campaign start, but I want to caution you against attempting to do any detailed outlining of your campaign beyond that point. You don’t know in advance what choices your players will make, and you’ll write yourself into a corner attempting to guess. Details that seem obvious to you can be utterly opaque for your players, and each crew of adventurers is an experiment in harnessing chaos energy. After all, you’re not writing a novel, you’re building a story with your players, and creating a detailed outline can suck the life out of that collaboration.

So, what should you write down?

You want short starting stubs of information that you can flesh out later as the players’ grow closer to them. Don’t write out the details of treasures and secrets of the Eastern Bandit lords, because, uh… what if your players decide to go West instead? What a waste!

Now, it’s true that in the example above, assuming you didn’t already set an expectations that the bandits were in the East, you could just move them, but if your players explicitly chose to go the other way, it’s a pretty cheap move to be like, “Surprise, the Bandit Lords are here too!” Or even worse, “Damn, guess you guys should have gone the other way…” That kind of approach will suck the momentum out of your campaign, and frustrate your players to boot.

Why? Because the players’ choices NEED to matter. If you want to fully immerse your players and fill them with wonder/horror/joy, [75% or more of what happens over the course of your games should be a direct consequence of the players’ choices. If they show mercy to an enemy, make sure that they see how that changes the enemy in the future, or if it doesn’t, make sure they show how that enemy does more harm as a result. Maybe they save someone or recover a stolen item. Perhaps now they have a bounty on their heads from whomever they thwarted in the process. If you take nothing else to heart from this guide, please let it be this. The players’ actions drive the story. Period.

Which brings us to our next important tip.

#7: NPCs Should Be People, and Your World Is Made of People #

So instead of pages of notes, dozens of dungeons, and a binder of planned encounters, you should instead focus your creative energy on defining the key levers that drive the events with which the PCs must contend. Which again, comes back to characters. In this case, the major NPCs. And NPCs are people.

People have opinions. They have needs, and they have wants. They have personal philosophies and their own sense of worth. And they have their own set of circumstances that influence the way they see the world. An NPC is no different.

I’m not saying you need a complex backstory for every innkeeper, stable boy, and merchant your players encounter, but in the case of your major NPCs (and perhaps whole factions) you need to know who and where they are, what they want, and what they are prepared to do to get it.

For example: Maybe you’ve got a warlord (we’ll call her Narra) trying to end the practice of slavery in a region, and her chosen approach is that she will use military might to conquer and unite the peoples of that area so that she can force this change. That tells you a lot about her, and honestly is a better guide for determining how she will react to the players than sketching out a whole game arc around that region that the players may or may not choose to pursue.

Did the PCs recently free a city from a tyrannical ruler, or even destroy a village in their attempts to save it? Narra may not even know that PCs were involved in that, but you can be certain she has an opinion on the event. Maybe she approves of the ruler being overthrown, or maybe he was a powerful ally of necessity and this has dealt a blow to her cause. Maybe the destroyed village was part of an important trade route her supply lines depend upon. Again, if Narra doesn’t know the PCs are to blame, it may change nothing about how she feels about them, but you should use the opportunity to make sure the players see the effects of their actions, whether positive or negative.

Again, you don’t know what choices your players will make, so don’t try to figure out a complex IF-THEN tree for how Narra will respond. As long as you know her motivations and limits, you can make that determination based off of what the players actually choose to do.

And who knows? Later on, they may discover that Narra’s war has an impact on the surrounding kingdoms’ politics, number of refugees, and economics. And if you do insist on having a BBEG for your campaign, that probably factors into their schemes as well. Take opportunities to show the interconnected nature of your world, and let the players see how their own actions can have results beyond their original scope.

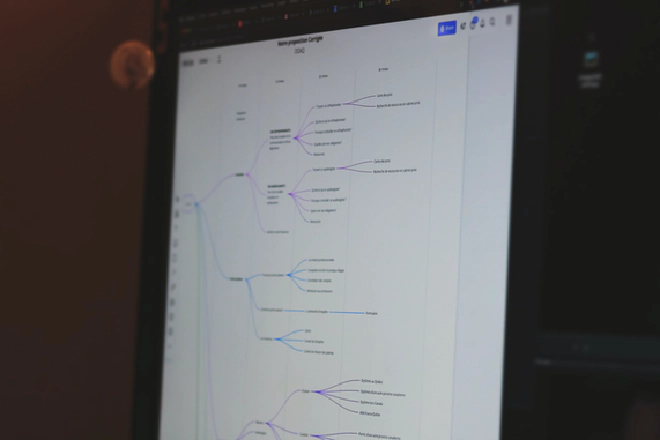

Consider using something like a mind map instead of a text document to do your writing in. This can help you avoid being too linear in your thinking, and makes it easier to visualize how different components of your world/story relate to one another. Or I don’t know, make a scrapbook. You do you. The tool you use is less important than your approach as a GM.

#8: The End Is An Avalanche #

Over the course of the campaign, there are going to be lots of quests, side-quests, sub-plots, and even a fair amount of tom-foolery to let loose the tension from time to time. But when it comes to your character arcs, and the conclusion of your story, try to pace your games in such a way that they all near their fruition around the same time. It doesn’t all need to be in the same session, but the end of the campaign should feel like dominos falling, as the characters scramble to keep up, racing towards either some sort of victory or tragic failure.

A PC attempting to find resolution with that newly-found brother? Have that be right before the battle with the big bad, or even as a consequence of that struggle. You got a player whose character started off trying to reclaim their family’s ancestral fortune, but now is debating if any of it is worth it given the joy of having their new friends? Try to have that be a choice they make right near the end. You may not be able to get everything perfectly synchronized for this; after all, the PCs may have very different personal goals. But the more you can align these points with a major narrative beat from one of the other arcs, the more collective impact they will have.

To properly choreograph these moments, and maximize their impact, you’re going to have to do something important. Something you should have been doing all along, but it’s so critical, I wanted to save it for last.

#9: You Need To Talk to Your Players #

For any of the above to work, you need to be checking in with your players regularly, both as a group and individually. Set aside some time at the end of each session to ask players how they felt about the session, and occasionally use one of your scheduled session times as a forum to get feedback about what people are liking, or are frustrated by, in the campaign so far.

You should also do this with your players individually. Set a calendar reminder for yourself to check in with them on how they’re doing, and to collaborate on how their character’s arc is progressing. Use that feedback to fix issues, identify fun new directions to take the story, and to pace that avalanche at the end effectively.

Communication and collaboration are the keys to running an amazing campaign, one that you and your players will talk about for years to come. Don’t miss the opportunity to make your next one rewarding.

Wizards of the Coast are notorious for cranking out overly lethal and formulaic campaigns due to a bizarre commitment to their “six to eight medium-to-hard encounters per game day” mechanic, which almost no group actually follows. You’ll hear folks argue that an encounter doesn’t have to be combat in D&D, which is true, but is also thinly veiled apologia. D&D’s mechanics, character stats, and writing style makes the intended logic of the guidance clear. It is puzzle traps and combat all the way down. Even Curse of Strahd, which is very well written and delightfully non-linear, only works if you cut out the insanely lethal “Death House” bit at the beginning. ↩︎

Lines represent things they absolutely do not feel comfortable with in the game, which can range from general concepts such as player romance to very specific “nopes” such as eye trauma. Veils are things that players aren’t comfortable playing out, but can be included if they are only implied or off camera. For example, a player might be ok with sex being something addressed in the game, so long as it doesn’t get played out directly. ↩︎

DAILY??? REALLY???! You lucky dog! ↩︎

I honestly don’t like the notion of a single BBEG for a campaign. It constrains the world to the scope of one individual’s desires, which as a GM, frankly bores me. ↩︎

Not to mention the fact that the Hero’s Journey involves the titular hero finding personal strength in isolation, which is going to be immediately complicated by the fact that it’s a group of adventurers who need to work together to succeed. ↩︎